Ever fancied penning your novel in a medieval castle? Or pouring over poems in a cabin in the woods? Working on your script in a little apartment by the sea? Maybe what you’re looking for is a writing residency. But what exactly is a writing residency? And how do they work?

What is a writing residency?

First things first: not all residencies are created equal. Some offer more than others. Some last as much as a year, some only last a week or so. Some offer individual accommodation, some offer shared. Some pay, some don’t. Some even expect the writer to pay to attend, but that’s not the sort of residency I’m going to be focusing on in this post (more on those further down).

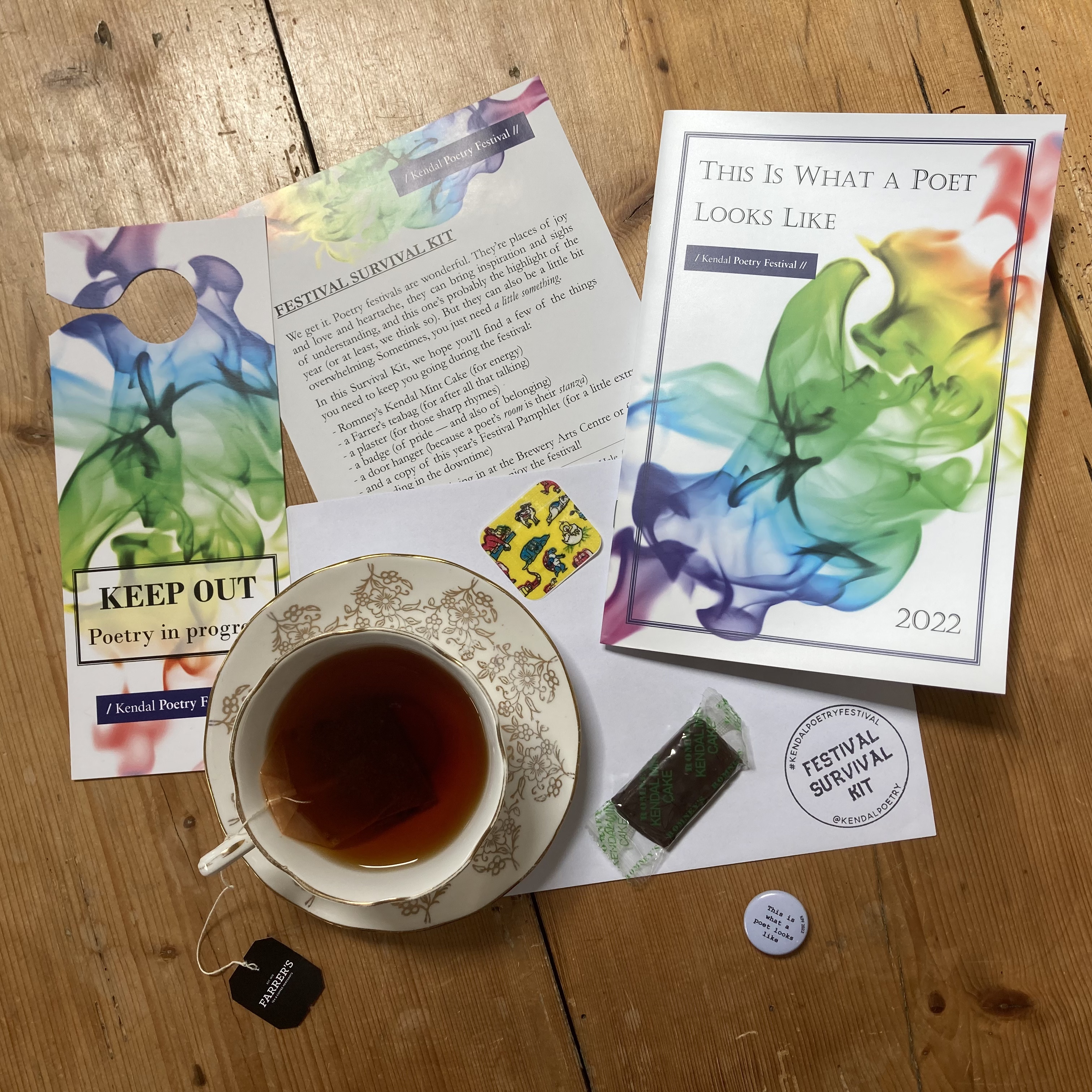

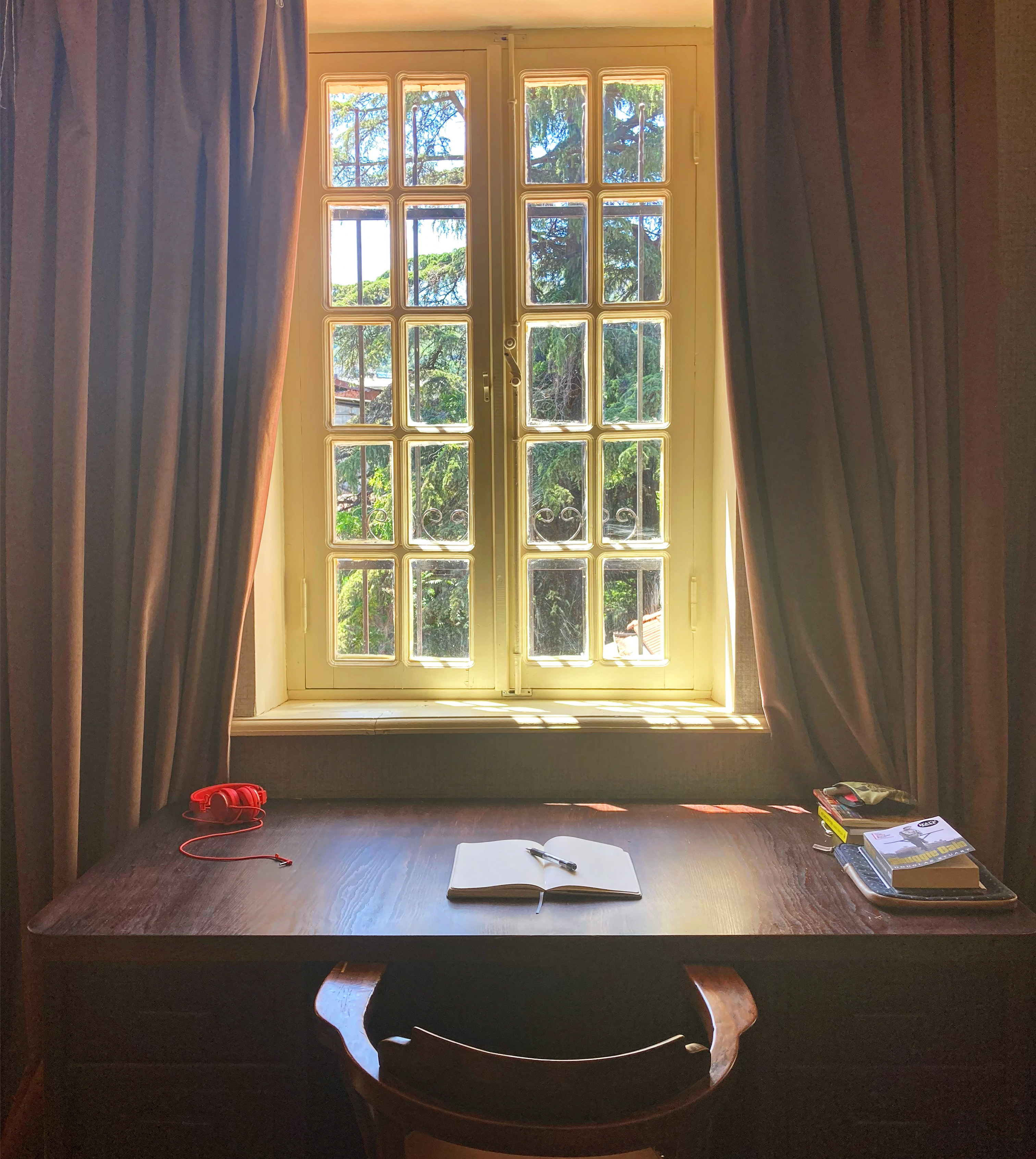

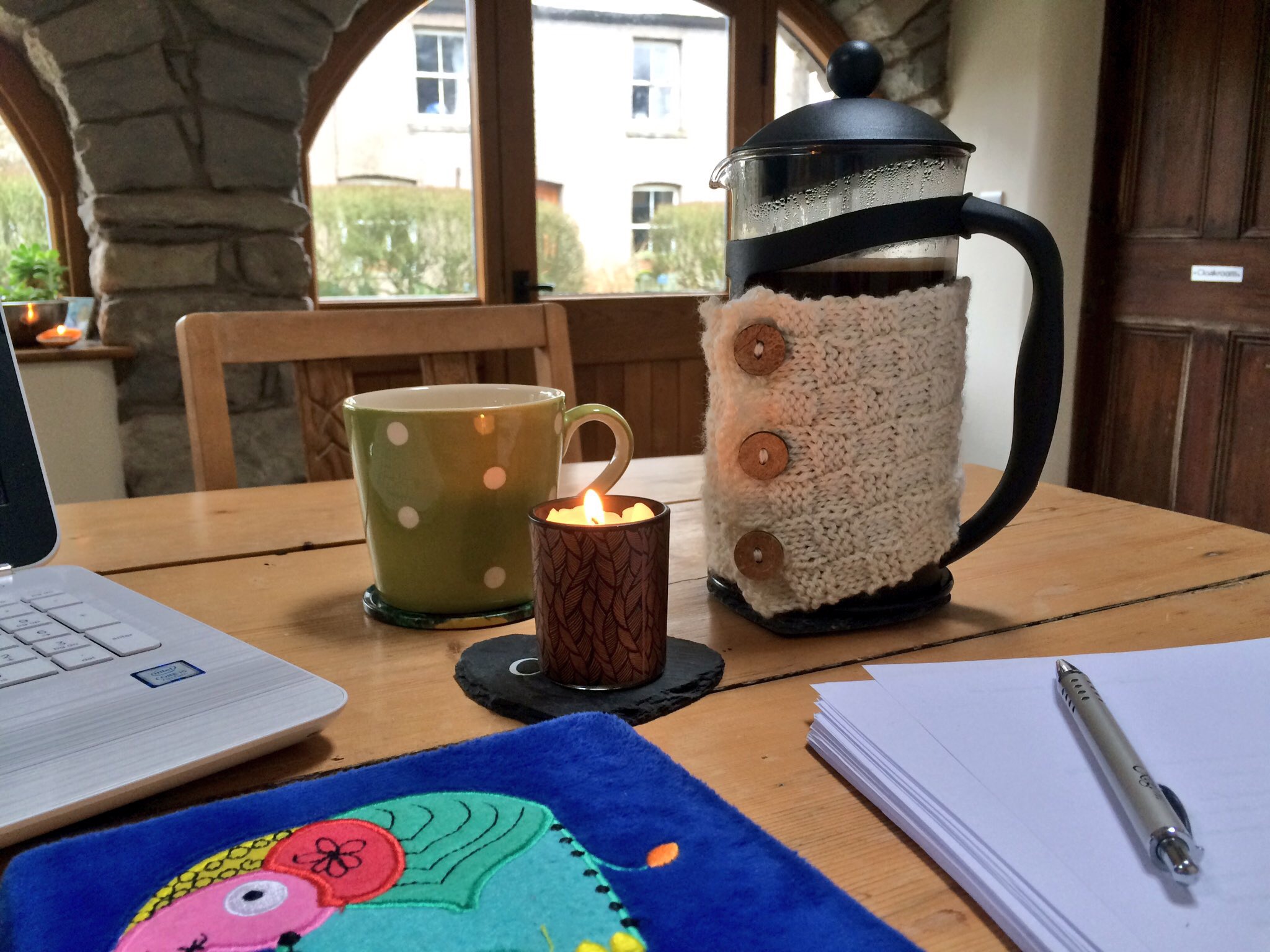

So what is a residency? Generally speaking, it’s a combination of accommodation & time to write. You get somewhere to sleep and somewhere to work. Sometimes, you also get meals, and / or a stipend, and / or travel expenses.

Sometimes, the residencies ask you to run a writing workshop, or to give a talk or something, in return. Sometimes you have absolutely no commitments other than working on your own writing.

I went on 3 residencies in 2019, and I’ve got another 4 lined up for this year. Here’s a quick run-down of what they offer(ed):

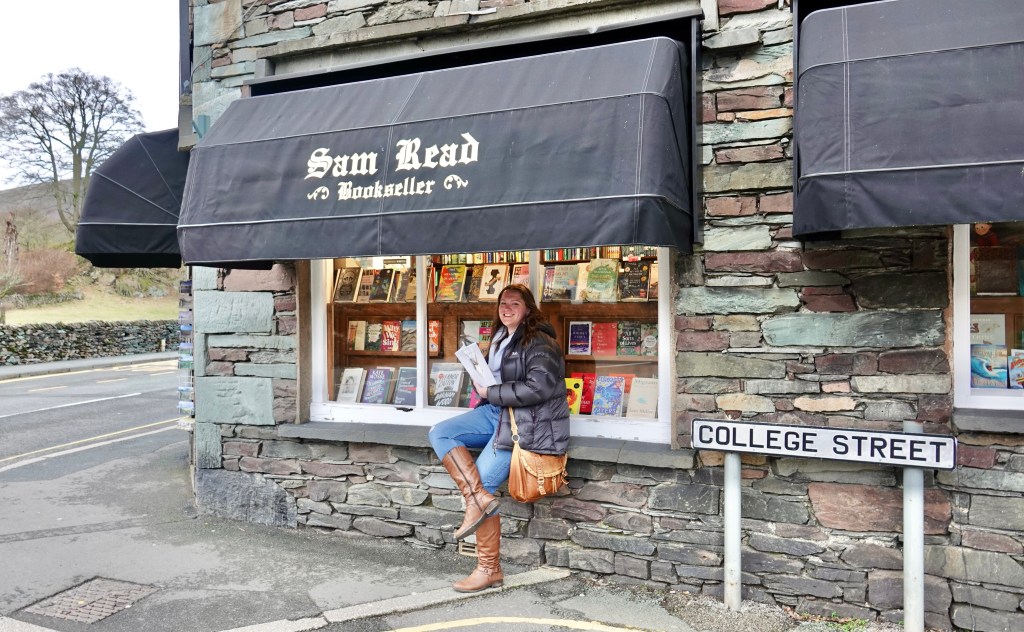

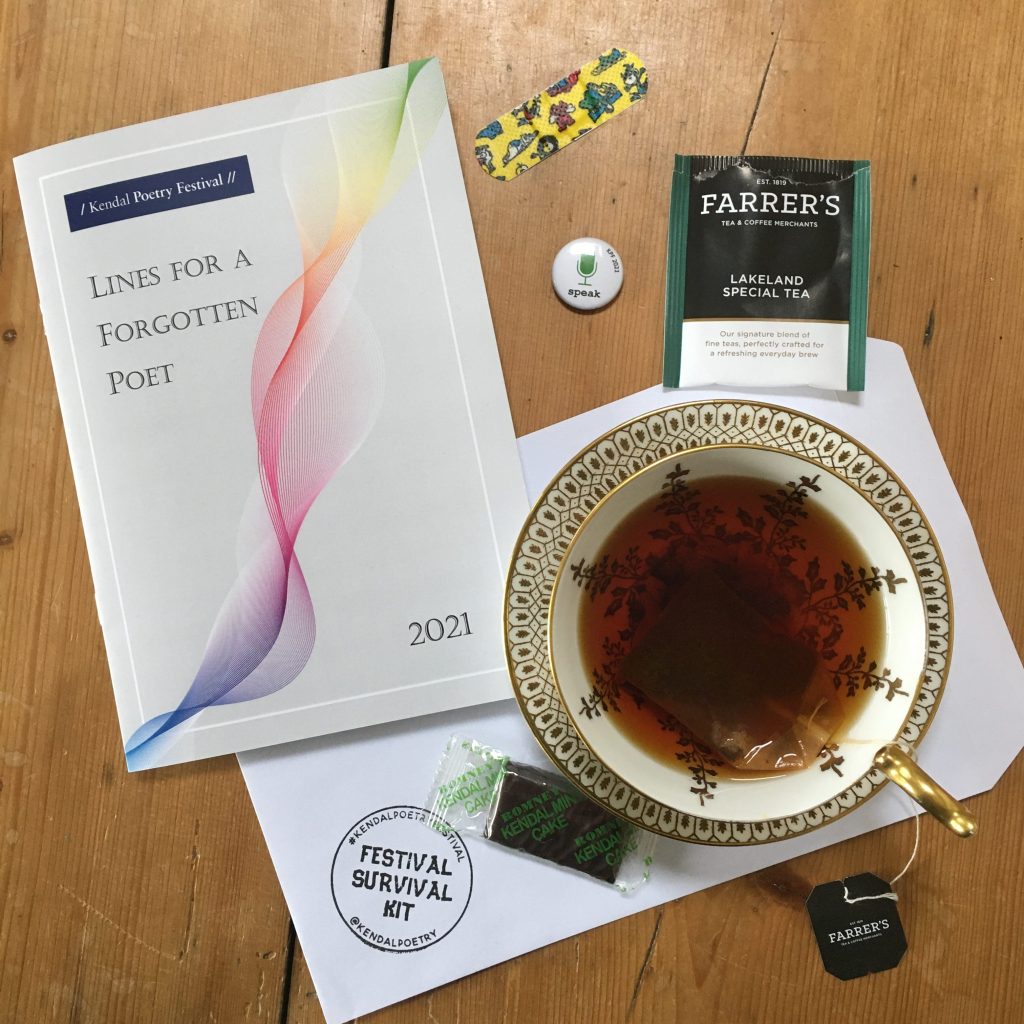

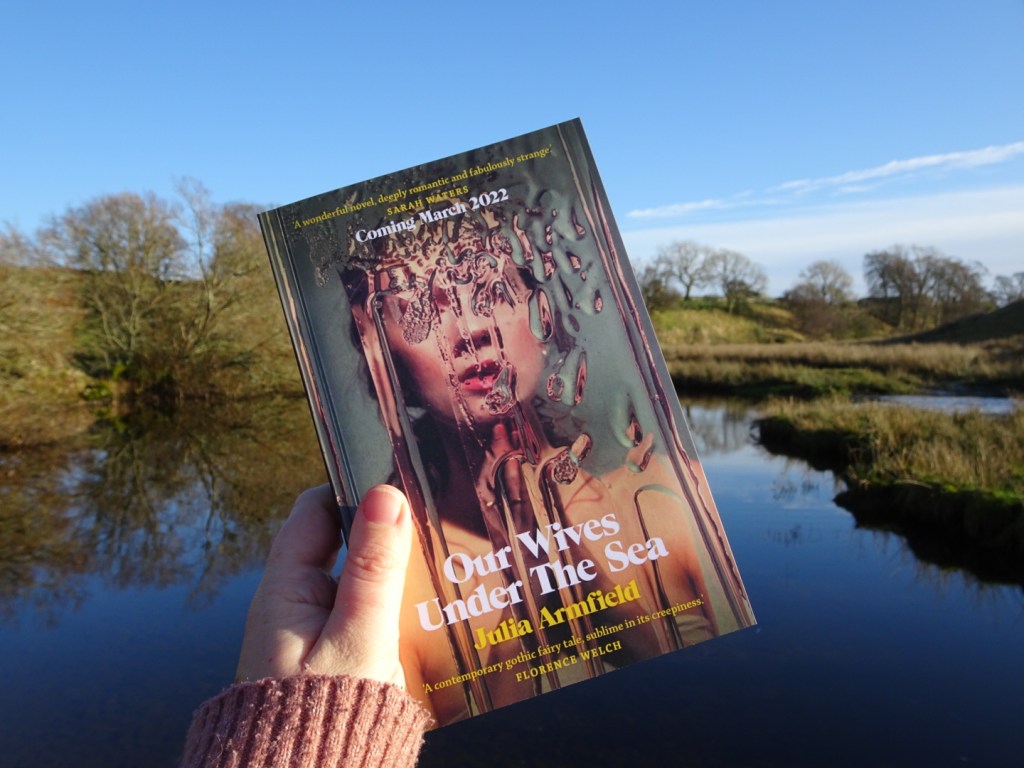

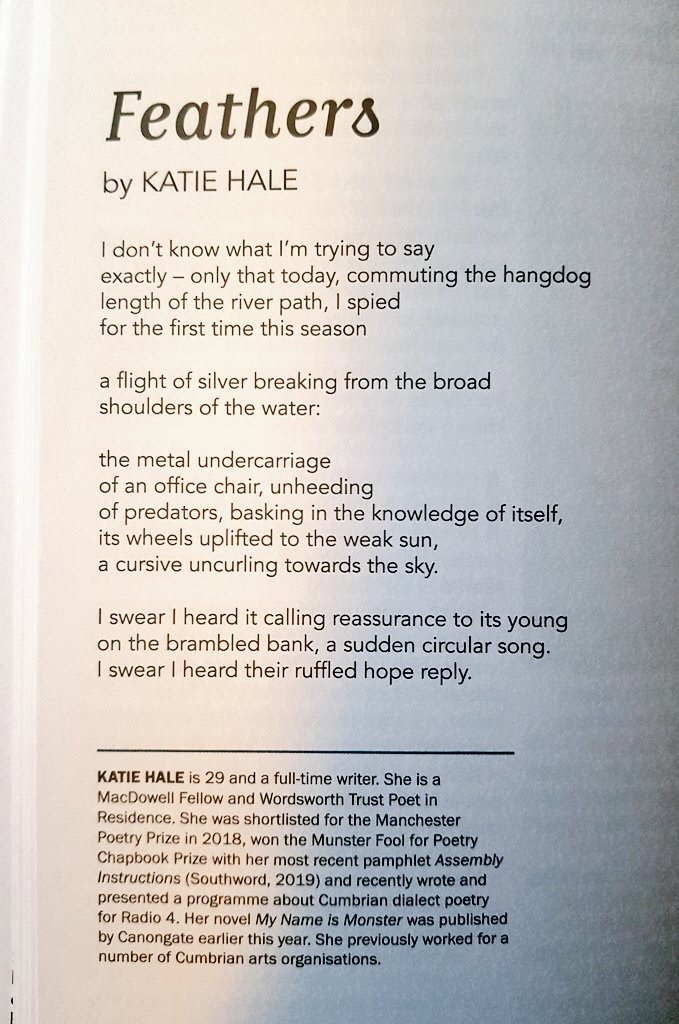

- The Wordsworth Trust Poet in Residence, Cumbria, England: a month; a private study-bedroom in a shared house opposite Dove Cottage; payment; required to give a reading & run 4 workshops.

- MacDowell Colony, New Hampshire, USA: 3 weeks; private bedroom in a shared house; a separate studio cabin in the woods; meals; travel expenses; no requirements other than writing.

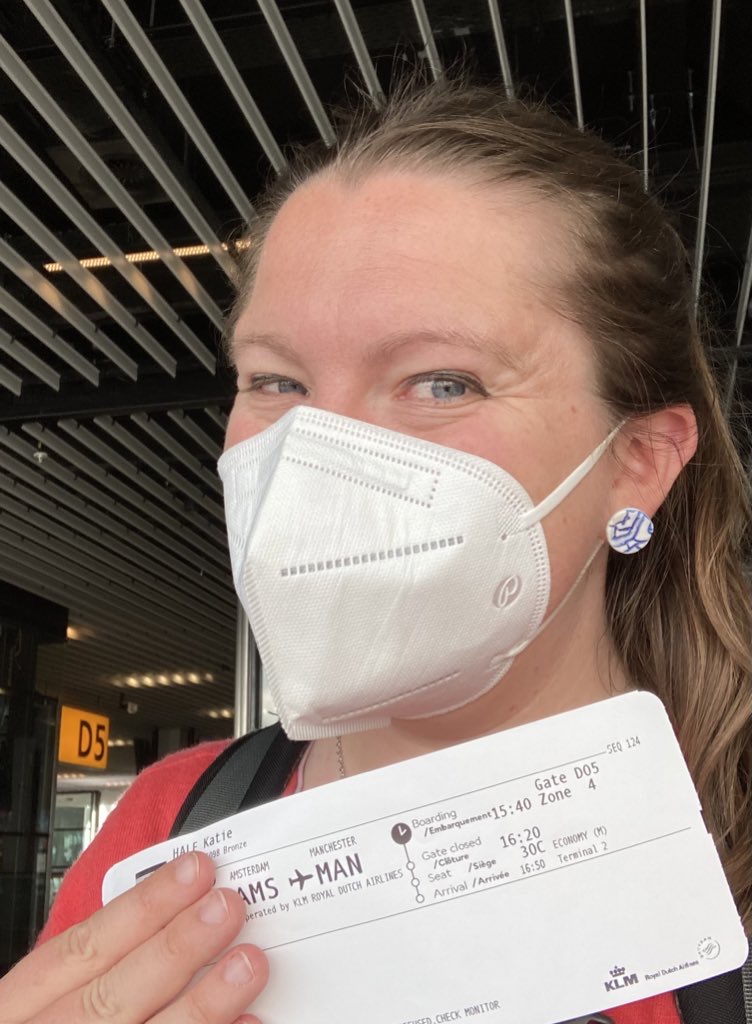

- Passa Porta, Brussels, Belgium: 4 weeks; private apartment in the centre of the city; travel expenses; stipend; participated in 2 translation workshops & wrote a blog post.

- Hawthornden Castle, Scotland: 4 weeks; private room in shared medieval castle; meals; no requirements other than writing.

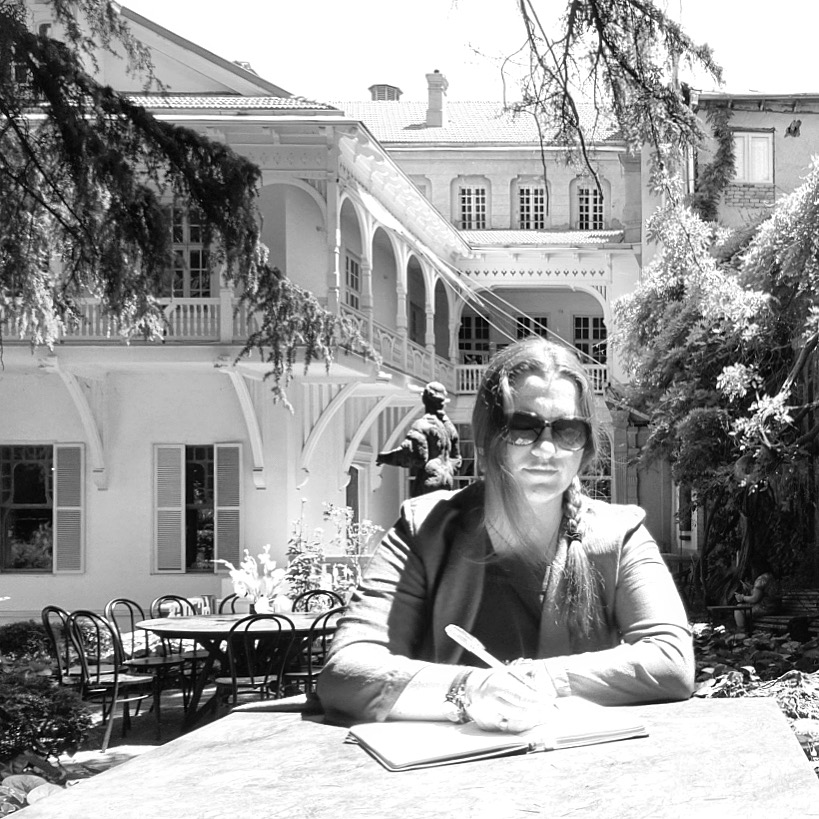

- KSP Writers’ Centre, Perth, Australia: 3 weeks; private cabin; stipend; required to run a workshop, attend a literary dinner & give a library talk.

- Gladstone’s Library, Wales: a month; private bedroom in residential library; travel expenses & stipend; meals; required to run a masterclass & give a talk.

- Heinrich Boell Cottage, Achill Island, Ireland: 2 weeks; private cottage by the sea; no requirements other than own writing.

Residency Round-Up: The Wordsworth Trust

Residency Round-Up: MacDowell Colony

What’s so good about residencies?

Residencies give you time to write, away from the pressures of everyday life. Whenever I’m on a residency, I switch on my Out Of Office, (mostly) prepare and queue up my blog posts ready to go, and ignore my admin. (Ok, I’ll be honest – I do sometimes check my emails, just in case. But I restrict my email-checking to the occasional evening, and even then I only reply to the absolutely urgent ones. At some residencies, such as Hawthornden, there isn’t any wifi anyway.)

It’s amazing how much extra time there is in a day when you don’t have to fill half of it with answering emails and trudging through invoicing & expenses & admin. Particularly if someone else is making all your meals for you, as is the case with some residencies.

My 6 most productive weeks of 2019 were the 3 weeks of my MacDowell residency, and the first 3 weeks of my Passa Porta residency. I wrote way more than I’d normally have written during that time, and when I looked back on what I’d produced afterwards, some of it was quite different to what I think I’d have written at home. For me, these residencies pushed me qualitatively, as well as quantitively.

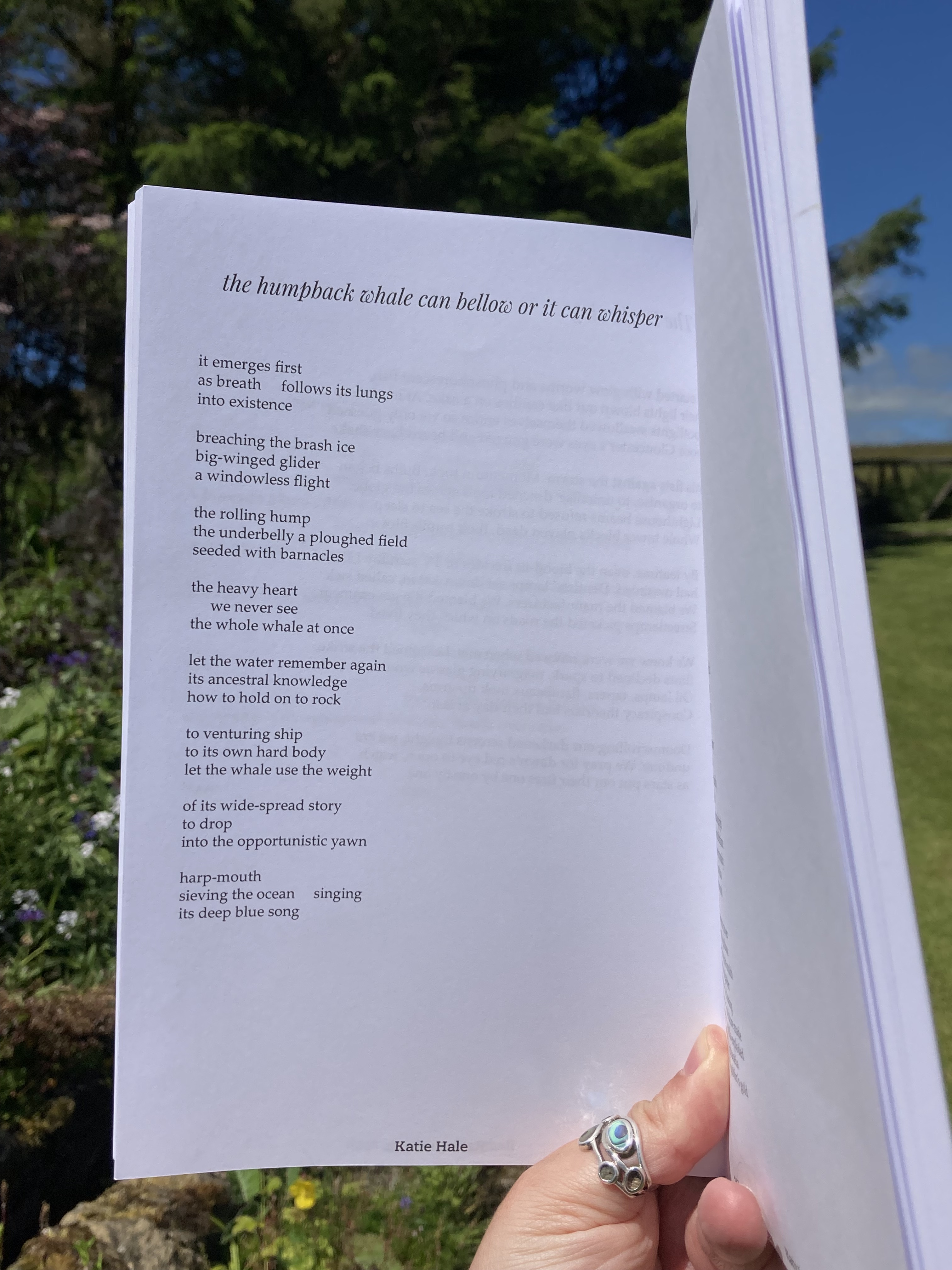

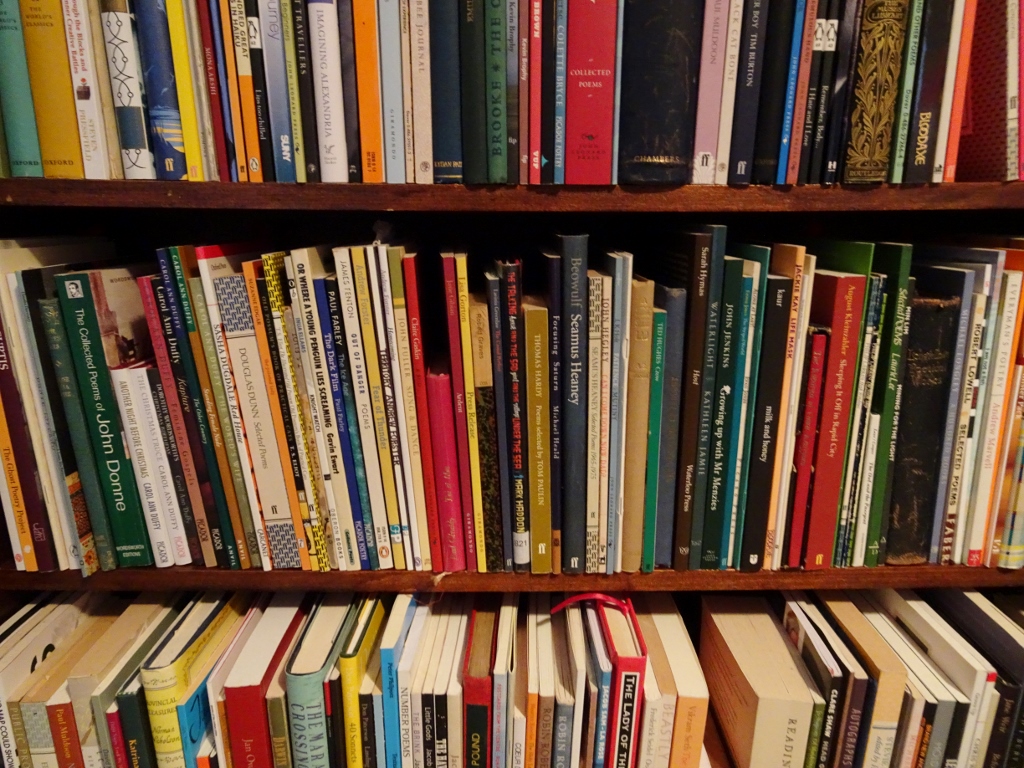

But residencies can also be time to read, and a chance to experiment with your craft. In contrast to MacDowell & Passa Porta, I wrote comparatively little during my Wordsworth Trust residency (though still probably more than I’d have written during the same period at home). What I did do, though, was oodles & oodles of reading – reading both poems, and books about writing poetry. I spent a lot of time thinking about the craft of poetry, and experimenting with my own style of writing – something which I’m sure contributed to my huge productivity at MacDowell a month later.

This is the sort of craft development that can easily get pushed to the side in everyday life, particularly when you’re having to write for commissions & deadlines etc, and so every poem has to be ‘good’; it can become difficult to make time to explore & experiment. Residencies can provide that time.

They can also be a way of meeting other writers – though this depends on the residency. For those residencies where there are a number of writers all there together (such as Hawthornden), it can be an excellent bonding experience, where everyone is working so intensively on their own manuscripts during the day, then coming together to eat and talk during the evenings.

For those residencies that are multi-disciplinary (such as MacDowell), it can also be a good way of meeting artists working in other forms, and of finding inspiration in conversations with non-writers.

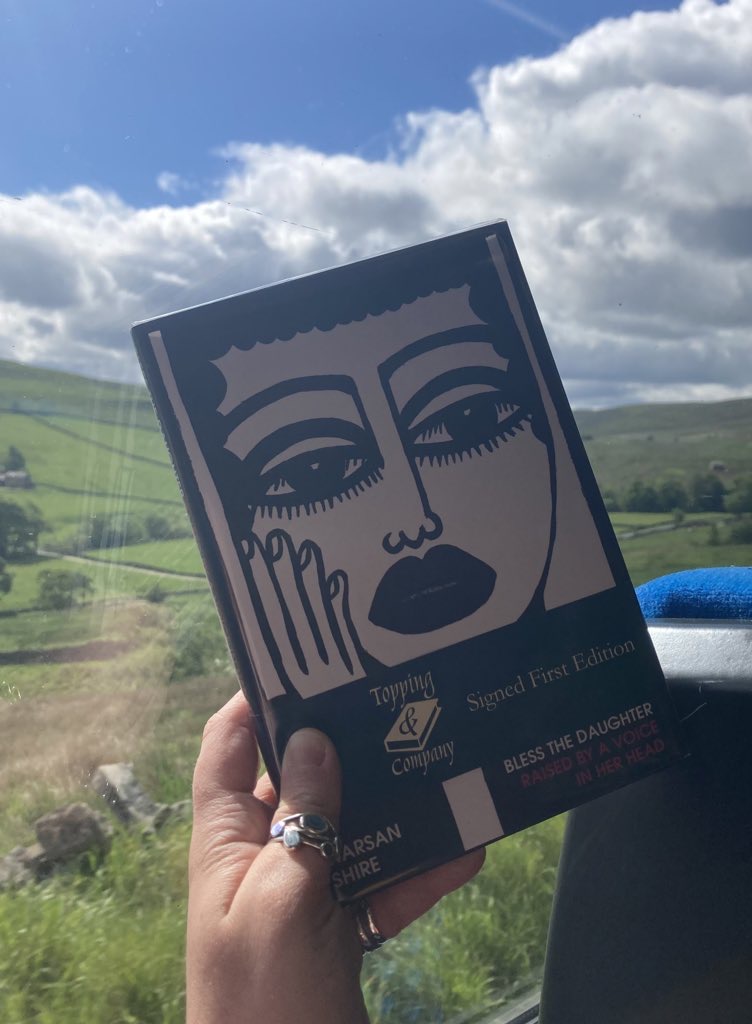

I’ll be honest, a large part of my initial motivation to apply for residencies was the opportunity to travel. Anyone who knows me will tell you that I love to travel, and residencies can provide a cheap way of doing that. If you can get a residency that provides travel expenses & accommodation, then you’ve essentially got a free trip to wherever it is that the residency is based.

Of course, residencies aren’t meant for sightseeing; they’re meant for working. But if you’re there for a reasonable length of time, then you’re going to need the odd day off anyway (trust me: residencies can be intense, and it’s good to break the cabin fever once in a while).

Another good way of exploring an area where you’re in residence can be to extend your trip. If your residency pays travel expenses, then there’s no reason you can find your own accommodation for a few days before or after your residency, and stick around to see the sights then.

Of course, beyond the tourism, travel & change of environment can be excellent for the work as well. Stuck on a manuscript, or just getting too easily distracted at home? A change of workspace could be exactly what the doctor ordered. And honestly, it doesn’t even have to be a beautiful cabin in the woods, or a medieval castle. I’ve had some of my most productive poetic breakthroughs in Travelodges.

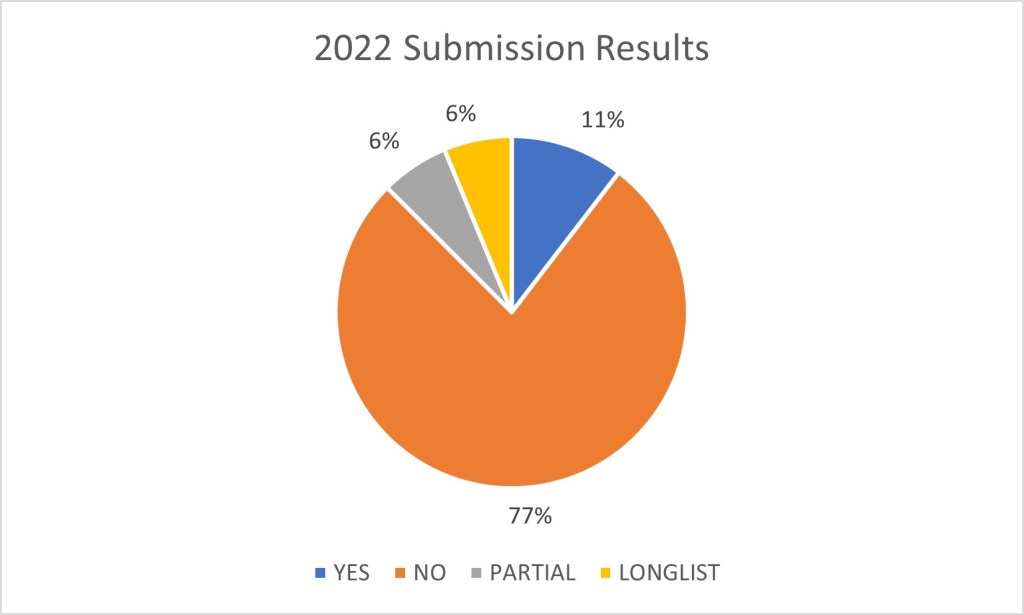

But let’s look at the financial side of things for a moment, too.

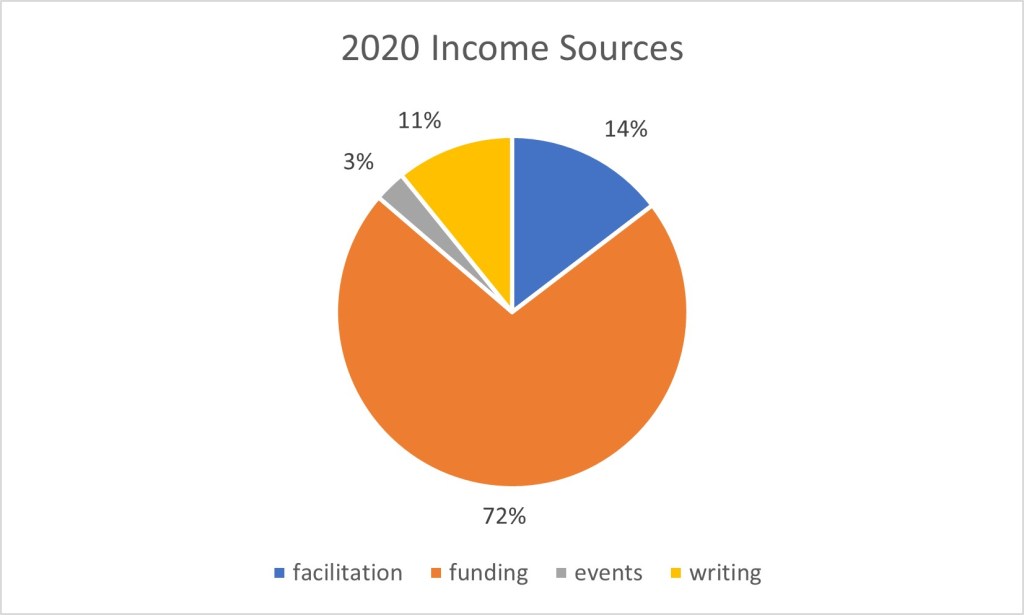

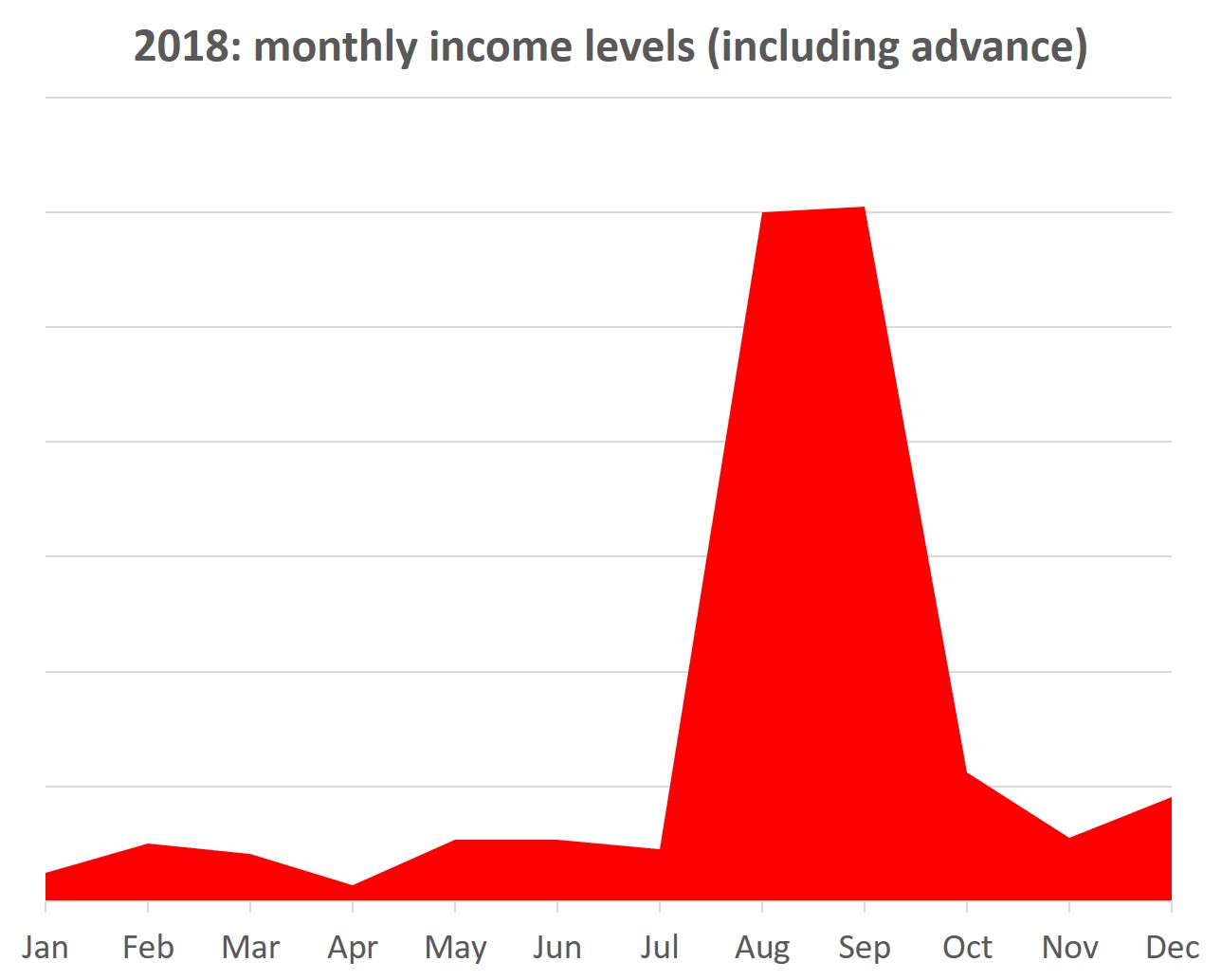

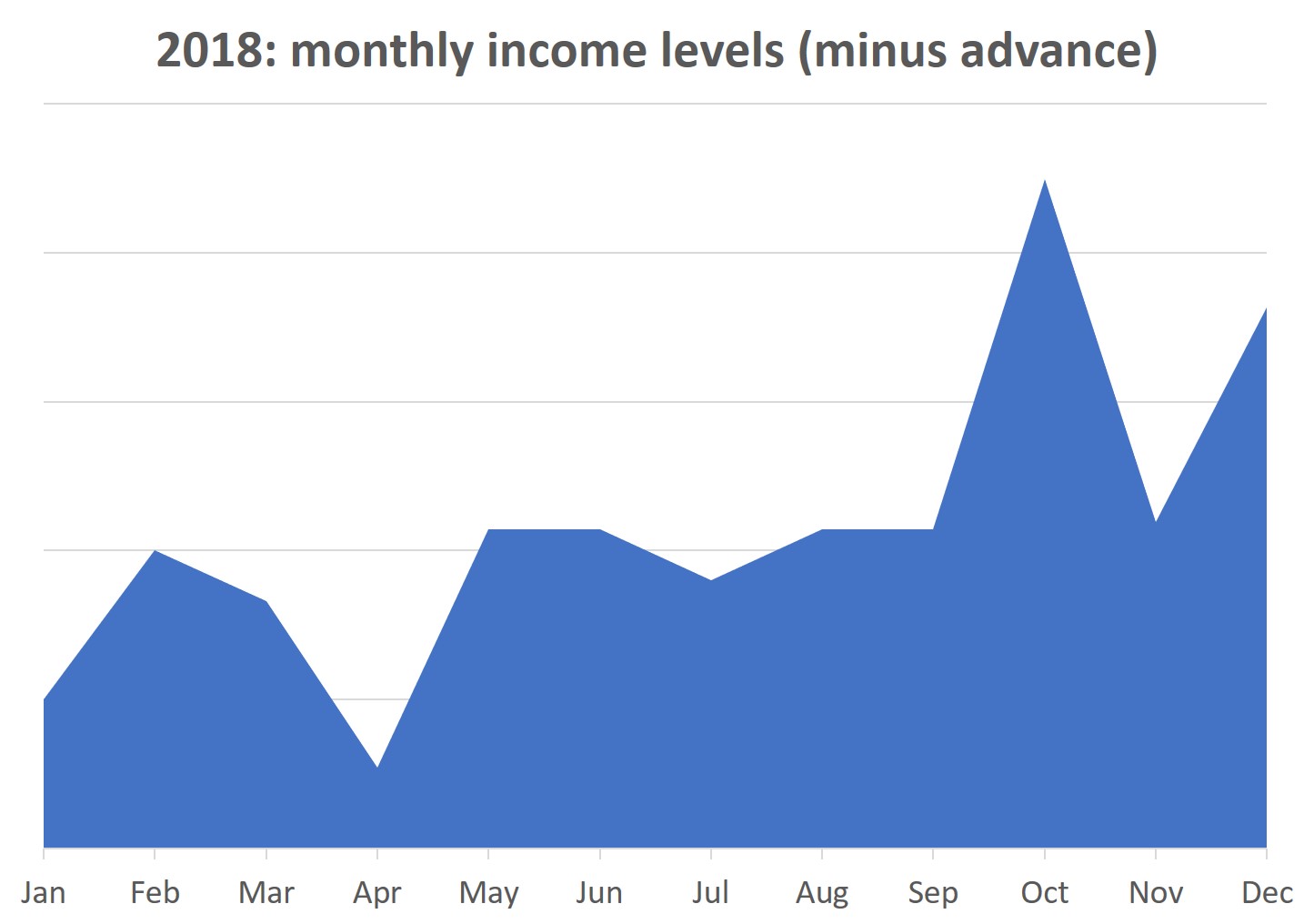

Some residencies pay a stipend – which is sometimes a token amount to help you buy pasta & notebooks, and is sometimes akin to an actual wage. This means that you can actually earn money by staying somewhere gorgeous and working on your manuscript. Depending on what you have in the way of expenses back home, it’s even possible to save some of this stipend money to fund even more writing time back at home. In 2019, residencies formed a not insignificant part of my income.

Even for those residences that don’t pay anything, they can still make financial sense. For example: I live alone, in an old house that’s kind of pricey to heat, which means that my bills can be huge. By planning residencies during the winter, I can go whole months without having to heat my house. I might not be being paid to attend the residency (though fingers crossed I’d eventually get an advance on the manuscript I was working on during it), but I’m also minimising my outgoings enormously.

5 Things About: Writing on the Move

What’s not so good about residencies?

Maybe by now you’re thinking it all sounds too good to be true. Obviously, nothing is perfect. For me, the positives of residencies have always outweighed any negatives. But I like to be honest on this blog, so here are some of the downsides to residencies:

When you’re in a place for a concentrated period of time, there can be a huge pressure to produce work. After all, you have this precious gift of time, and if you don’t use it to create something incredible, then doesn’t that mean that you’ve wasted it?

This negative aspect is largely self-inflicted. After all, it’s extremely rare that a residency will ask you for a quantative breakdown of what you’ve produced during your stay. Which means that the strategy for dealing with this pressure has to come from you as well. After all, you know your ways of working better than anyone. But just remember that you don’t have to write 17 novels and 53 essays during your residency. It’s just as vital to work on your practice in other ways, by thinking, by reading, and by exploring the way that you work.

Although, speaking of productivity, it is also possible for a residency to go the other way: that you’re so overwhelmed by the residency’s other requirements of you (running workshops / giving talks etc) that you end up with very little time or headspace left for actual writing.

This is largely down to the residency, to make sure that they don’t overload you. But you should also make the effort to be aware of what’s required of you before you start, and to raise any concerns you have about workload with the residency coordinator ahead of time. This obviously doesn’t mean you can be a diva about it – the occasional commitment is fine, particularly if the residency is paying you a fee or stipend on top of the accommodation. But if the commitments outweigh the writing time, or if they keep being piled on beyond what you originally agreed to, then maybe it’s time to say something.

The other issue I want to talk about is loneliness.

Writing residencies can be intense, and they can also be lonely. Even when there are multiple writers / artists on the same residency, you can end up spending a lot of time inside your own head. And when it’s just you in an apartment, writing all day and reading every evening, then that loneliness can be hugely amplified.

Think of it like this: you’ve gone to a new town or city, where you don’t know anybody. You’re willingly spending hours (if not days) at a time shut up in your room or house or apartment. You don’t speak to anyone, much, except maybe the person on the checkout in the supermarket. You may not even speak the local language.

Now imagine this for four weeks. It probably isn’t long enough to make solid friends, the way you would if you were moving to a new city for good. But it is a long time to spend away from your normal social groups.

Of course, everyone reacts to isolation differently. There’ll be some people reading this, for whom even the thought of a few days without talking to anyone sounds horrific. There’ll be some of you who think a few weeks’ isolation sounds idyllic. At the end of the day, we all know our own limits – or at least we suspect them.

Take me, for example. I think I’m a fairly independent person. I’m an only child, so we never really had a houseful growing up. I live alone. I also live rurally. I work freelance, so I don’t have colleagues who I interact with on a daily basis. I’m generally faily happy in my own company, and I like knowing that I have my own space if I need to get away from it all.

But, during part of my residency in Brussels last year, I felt very, very lonely.

I was fine for the first two weeks, after negotiating the first couple of days of settling in – difficult whenever you go anywhere new. By week 3, I was starting to miss friends & family, but was still managing to put that aside to focus on work. I’d also starting going for days and afternoons out to explore a bit more, and to force myself out of the apartment. But by week 4, I was honestly a bit of a mess. I missed conversations with people. I missed the sort of interaction that comes from knowing someone really well – or from getting to know someone through shared intense experience.

Don’t get me wrong: the residency was amazing, the staff at Passa Porta were utterly lovely, and Brussels is a stunning city. I just realised that 3 weeks is pretty much my limit for that kind of isolated residency.

Which is fine. I learned something about myself during the course of the residency. I now know that I can discount any residencies longer than 3 weeks, if there aren’t other artists or writers in residence at the same time. I discovered the limits of my loneliness.

How to survive a writing residency:

That all said: what’s my advice for anyone going on a residency?

Do your research before you go. Because residencies can be so varied in terms of what they offer, and who they cater to, it’s worth knowing exactly what you’re getting yourself in for beforehand. This means there shouldn’t be any nasty surprises when you get there, and also that you can prepare for any talks & workshops before you go, so they don’t cut too much into your precious writing time.

Go with a project in mind. Remember that pressure to produce that we were talking about earlier? This can be exacerbated if you’re the sort of writer who works on more than one project at once. If you’ve only got the one residency, what do you start with? Your novel? Your poetry collection? Your short stories? Your epic fantasy saga spanning seven volumes? Do you try to dedicate a little bit of time to each? Knowing what you want to achieve from the outset can help you avoid wasting time on indecisiveness, and allow you to hit the ground running when you arrive at the residency.

Speak to people. A good way to combat the possibility of loneliness is to actually speak to people. This is obviously easier if it’s the kind of residency where there are multiple people there at once. But even if you’re on your own, make an effort to find people to talk to. Fellow writers. That person in the cafe. Even just a brief exchange with the person behind the counter in the shop can help with the feelings of isolation.

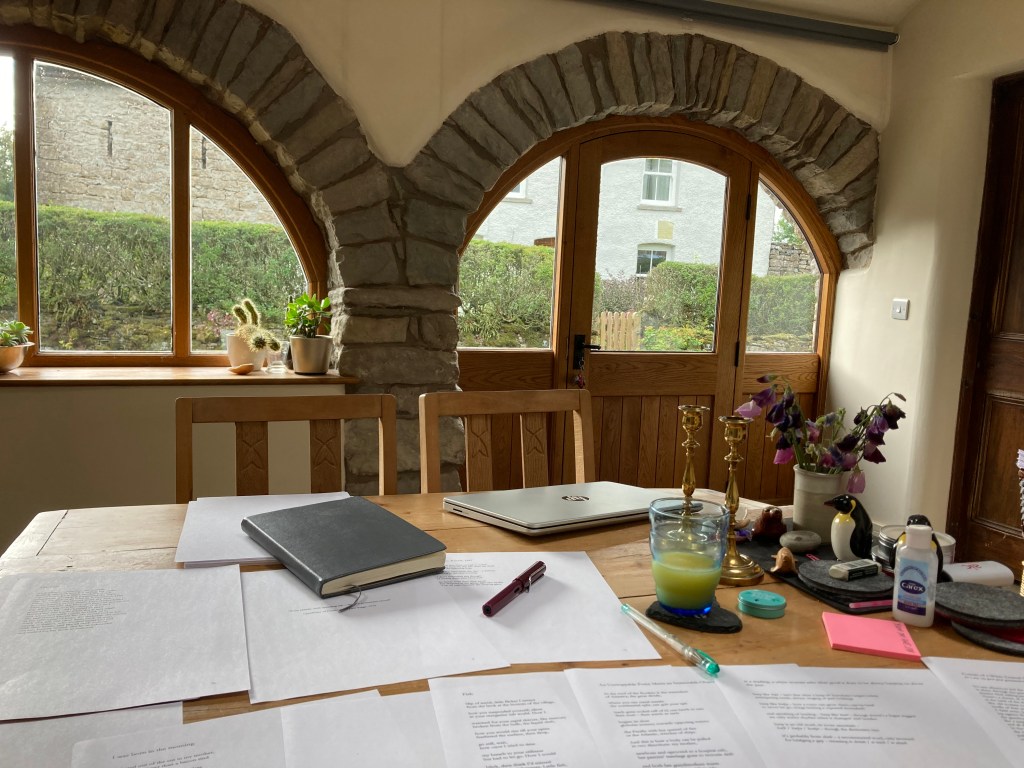

Take breaks. Yes, you’re there to work, and it can feel a bit like every day needs to be a 12-hour writing marathon, stopping only for toilet breaks and coffee. But that isn’t a sustainable way of working, and slowly concentration will begin to wane. Take breaks to read a book, to go for a walk, to sit in a cafe and drink coffee you haven’t reheated 3 times in the microwave. It’s a way of rejuvenating your energy – and it’s amazing how many Eureka moments can come when you actually step away from the writing desk.

Get out and about. By which I mean: don’t just take breaks in the immediate vicinity of your residency, but get even further away from the writing desk from time to time. During my MacDowell residency, a group of us took a whole day off to drive to a nearby town and try our hands at an Escape Room. It was completely unrelated to anything any of us were working on, but was also the best thing we could have done, to break that feeling of cabin fever we hadn’t even realised was beginning to set in.

Don’t beat yourself up if you’re not hitting your word counts. Yes, you’ve come with a specific project in mind, and you probably have goals you want to achieve while you’re in residence. But, while I absolutely believe that half the battle is just showing up to write, I also know that it isn’t a certain thing either. Sometimes, however hard you smack your head against your notebook or stare down that blank Word document, the words just won’t come. And that’s fine, too. You can have blank spells during a residency just as much as you can at any other time. The beauty of the residency is that you still have all that free time for creativity – so you can use it to read, or to freewrite, or to go for a walk and just think through your creative project. You can still be working, even when you’re not actually writing out words.

Pack snacks – and maybe a bottle of wine or two. This is a personal one, but I’m a big one for snacking, and I find it really hard to work if I’m hungry. So if I know I’m going somewhere that might not have easy access to a grocery shop, I always find it’s a good idea to stick a bag of biscuits in my bag – just in case. Even if I don’t end up eating them, I just like to know they’re there on the offchance I might need them. Plus, they’re a great way of breaking the ice. And the wine? Again: wine is nearly always a good way of making friends!

What to watch out for:

I said at the start of this post that not all residencies are created equal. The truth is that some offer much, much more than others. It isn’t always the case that the most respected residencies offer the most – but it is often the case that the less respected (and often less conducive to creativity) can actually take the most from the writer. The best way to avoid any upleasant surprises is to always read all the information available before you apply – just so you know what’s what.

A few things I’ve come across, which aren’t always bad, but which need to be noted, are:

Shared accommodation:

It’s quite common for residencies to offer writers a private bedroom / study-bedroom in a communal house, which may have shared bathrooms and communal workspaces – though you’re generally free to work in your room if you prefer privacy.

But I have also seen some residencies that only offer shared bedrooms (shared with another resident / residents, who you won’t meet till you arrive). I’ve even heard report of a residency that expected the writers to share a bed! Personally, I don’t think asking strangers to share a bed is ever appropriate, but I suppose the shared bedrooms thing is a matter of individual preference. If it’s something you’d be fine with, then go for it. Personally, I need my own space to work in.

Application fees:

A number of residencies charge a fee for you to apply. Usually, this is to offset the cost of processing the applications. After all, an individual residency might receive hundreds of applications, and somebody needs to process all of those, to check eligibility and ultimately to make a decision. That person probably needs paying, hence the application fee. Sometimes it can also go towards funding the residencies slightly, in the same way that the prize pot for a writing competition might be funded by the entry fees. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing – some highly respected residencies charge a fee to apply. It’s just something to be aware of before you decide whether apply, so that you can budget it into your decision.

Fee-paying residencies:

I mentioned this at the start of the post, and I want to talk about it here, because some residencies not only charge a fee to apply, but also charge a fee to attend. Sometimes this is nominal – just enough to cover a cleaner’s fee, or maybe put something towards electricity bills. But sometimes the cost can be as much as (or even more than) the cost of a hotel.

Again, there’s nothing wrong with paying for a room / apartment / cottage to go and write in, but I would argue that this is something different from a writing residency. I would argue that this is more like a self-guided retreat – like the kind offered by Arvon & by Gladstone’s Library. You pay your money, and in return you get to stay in a peaceful & supportive environment, and work on your manuscript.

But the thing about retreats like these is that they’re not selective. By which I mean: anyone can book and go on one, in the same way that anyone can book a room in a hotel. Again, that’s absolutely fine. There are hundreds of great reasons why these models work, and why you might want to pay to isolate yourself and focus on your manuscript – many of them th same as the ones above in this blog post.

However, if there’s a selective application process involved, and then you have to pay the full cost of the residency in order to attend, then I always wonder: why not just book into a hotel instead? Why bother with the whole hassle of writing & submitting an application, then waiting to see if you’ve been successful, when you can just book a retreat at Arvon or Gladstone’s in minutes – and know what you’re getting as well?

I’ve even seen so-called residencies that charge writers a fee to apply, and then also charge an astronomical amount for the writer to actually attend the residency. That’s like paying £20 to be in with the chance of booking an apartment on Airbnb, then having to wait 6 months to find out if you got it or not. Why would you do that?

Fortunately, there are plenty of residency opportunities that don’t try to make lots of extra money from the writer, and that aren’t commercial retreats masquerading as exclusive residency opportunities. So as long as you do your research, there should always be a residency that will suit the needs of each individual.

Ok, so where can I go?

There are residencies all over the world, and far too many to list here, even if I did know them all. I’ll start with the ones already mentioned in this post:

- The Wordsworth Trust Poet in Residence is in Grasmere, Cumbria (UK), and has so far been running every couple of years. They announce call-outs for applications through the e-news, so it’s worth signing up to their mailing list in their website footer.

- MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire (USA) has regular call-outs for applications.

- Passa Porta in Brussels (Belgium) runs its own writing residencies, which can be applied for directly. For UK-based writers, they work with the National Centre for Writing in Norwich, and applications are announced through their website instead.

- Hawthornden Castle, just outside Edinburgh (UK). EDIT: you can now apply for Hawthornden online! Check our their website for the new application process.

- The Katharine Susannah Prichard Writers’ Centre is in Perth (Australia), and runs a series of residencies for writers at varying levels of experience. These are open for application on an annual basis.

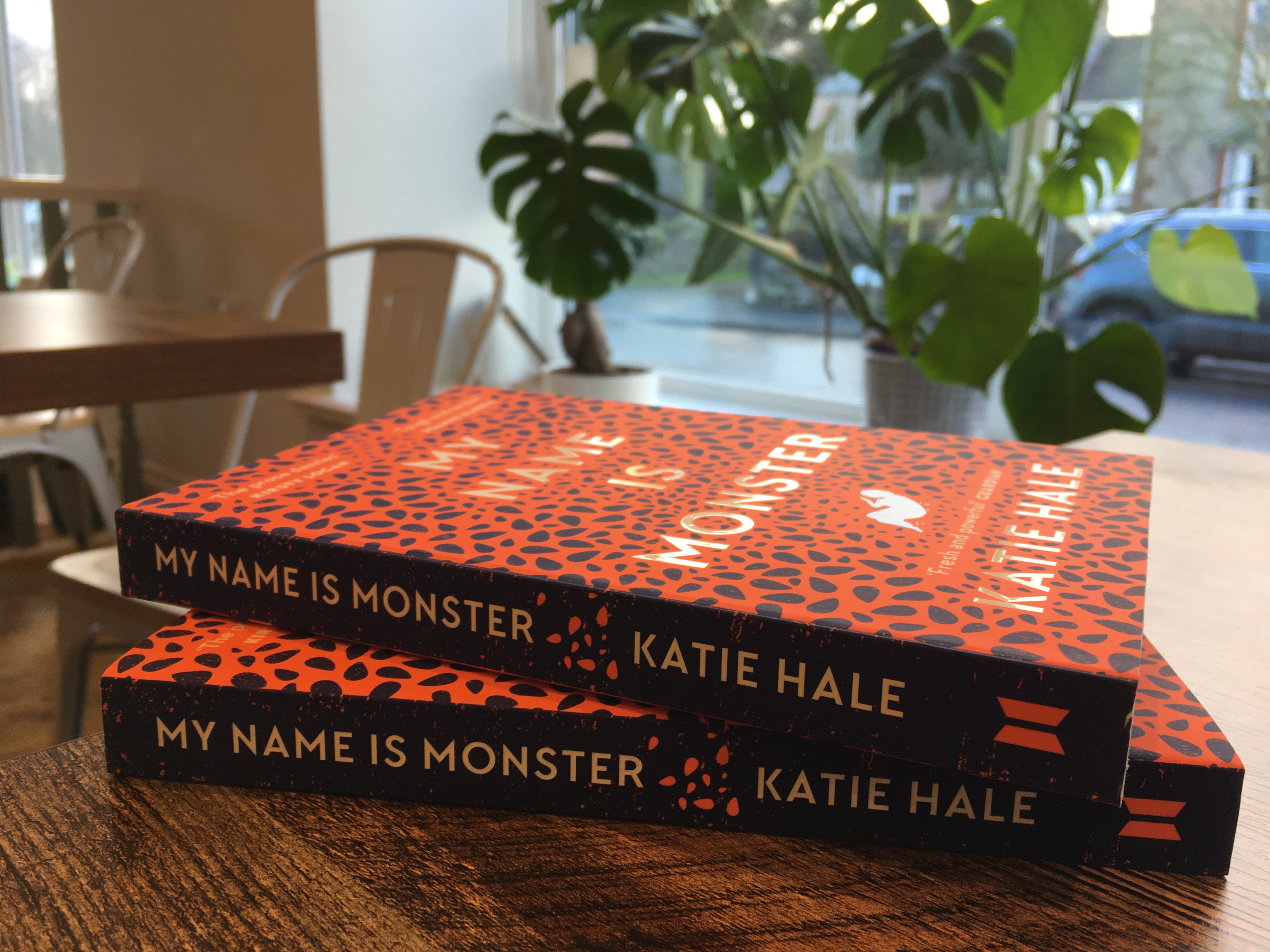

- Gladstone’s Library is a residential library in Wales (UK), which means that anyone can pay to stay there. But if you’re looking for their writer in residence programme, then this is an annual application process, based around a published book.

- Heinrich Boell Cottage is on Achill Island in County Mayo (Ireland), and is another one that requires a physical application. The deadline each year is the end of September, for a residency the following year – however, it’s worth noting that I didn’t receive a reply on my application till October the year after I submitted it (in the July), so this system may not be completely foolproof.

But of course, there are hundreds of other places to look for residencies. Good places to start your search might be:

- ResArtis is an online database of residencies. It allows you to search for residencies with current application opportunities, as well as to filter by artform, accommodation type, and geographical location. Be aware that this website also features residencies where the writer has to pay to attend, so be sure to read all the details before you decide whether to apply.

- Simliar to ResArtis, the other one to check is TransArtists. This online resource also allows filtered searches, and also features fee-paying residencies alongside ones where the writer doesn’t pay.

- Arts Council England runs two mailing lists: ArtsJobs and ArtsNews. These sometimes advertise residencies, so it’s worth signing up to them. It’s also worth signing up to the relevant equivalent mailing lists if you’re based in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland, too.

- Sign up to the mailing list of your regional writing organisation. For me, this is New Writing North, who are based in Newcastle. They also share residency opportunities, as well as lots of other useful info.

- If you want to travel, then periodic checks of the opportunities page on the British Council website aren’t a bad idea, either, as sometimes these include residencies & travel opportunities for individual writers.

- Another option? Sit down one evening with a couple of hours to spare, and a big glass of wine, and google variations on ‘writing residencies’ or ‘writer in residence opportunities’. Keep a list of anything that comes up, whcih you think might interest you.

If you’re applying for a residency, or you’re off to participate in one, then the best of luck! And in the meantime, here’s my favourite list of ‘residencies’ for you, from the New Yorker:

The New Yorker: Little-Known Writing Residencies