Novels are long. Really long. So long, that even if you’re full of ideas & enthusiasm when you start writing one, there’s almost definitely going to come a point when you’re not going to be quite as certain.

Sometimes, this is just a case of motivating yourself. After all, 70,000 words plus of writing, rewriting and rewriting again is a lot of time to keep yourself engaged. You’re bound to get frustrated with it from time to time, and it can be so easy to find a million things you’d rather be doing than writing your novel: baking; cleaning the windows; answering emails; scrubbing the toilet with a toothbrush… It’s a case of reminding yourself what you love about the novel you’re writing, and then making yourself get back to it.

But sometimes, it isn’t just about making yourself a big pot of coffee and chaining yourself to the desk. Sometimes, you can be hugely motivated to write, and yet still find yourself stuck in a particular scene. There are hundreds of reasons you might find your story isn’t really going anywhere. But there are also ways to help yourself over the hurdle of that difficult scene.

1. Go back to basics.

If I’m stuck on what’s going to happen in a scene, I often find it’s because I haven’t done enough preparatory work. Often, this boils down to me not knowing my characters well enough. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing – every writer works differently. Some writers plan everything in meticulous detail, constructing a ‘beat-by-beat’ of each scene, so that they know exactly what has to happen when, and then they just have to write it. Some writers go in knowing absolutely nothing. They start with a phrase or a first line or a vague idea, and build the whole thing up through the drafting process.

Personally, I’m somewhere in the middle. I like to plan just enough so that I have a vague idea of what’s going on, but not so much that there’s nothing left to discover in the writing process. I think of it a bit like walking through a tunnel under a mountain. I don’t need to see the whole route, but nor do I want to be blundering about in the dark. As long as I can see the next few feet in front of me, and have a vague idea of where the tunnel might bring me out, then that’s fine.

The good thing about this way of working is that I’m always getting to know more about my characters, the whole time I’m writing them. The less good thing is that I don’t know everything about my characters when I start writing – which means that sometimes, I have to go back and do some of that ‘preparatory work’ part way through the drafting process.

Often if I’m stuck, it’s because I’ve lost sight of what my character wants.

Everybody has something that drives them. Most of us are driven by multiple desires at once – some short-term (I’m cold and want to get warm) and some long-term (I want to be the first woman on the moon). The chances are, you’ll already have figured out what your character’s long-term desire is, during the planning process. But in the individual scene that you’re stuck on, maybe that long-term desire isn’t what’s driving them, and they’re being driven by something much more short-term. Maybe they have two or more conflicting desires – after all, most of us do. But in almost every moment, there’s going to be a desire that comes out on top.

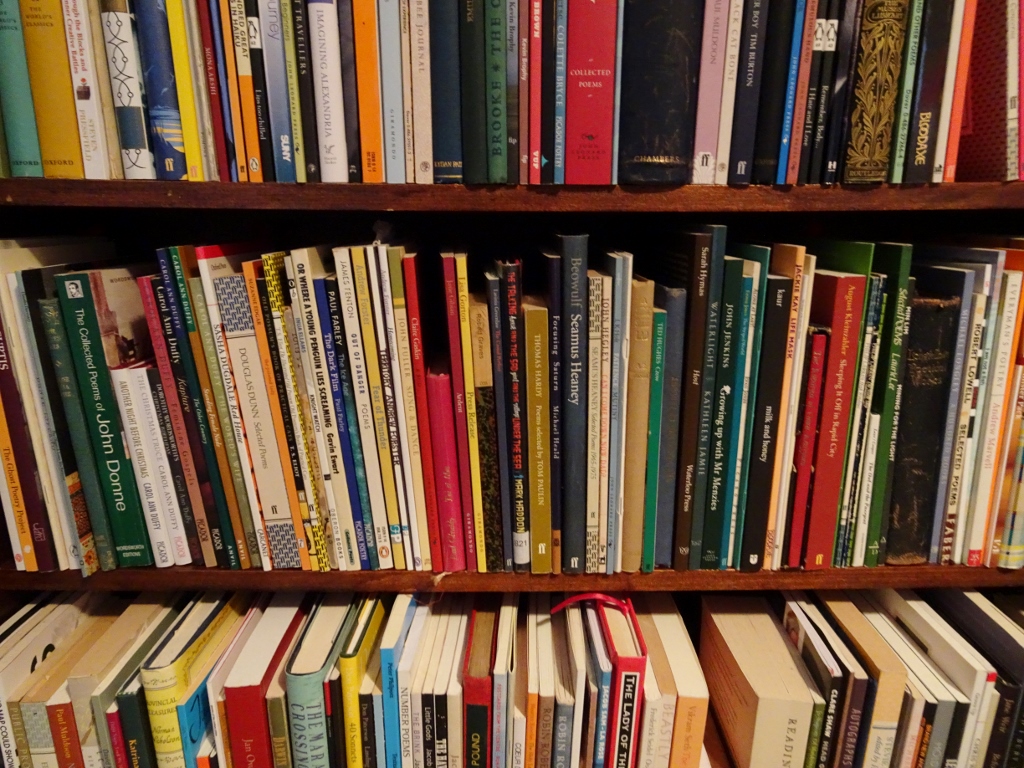

One of the best books I’ve ever read, for understanding character-building, is Will Storr’s The Science of Storytelling. I’d recommend it for anyone wanting to understand character and build up a character-driven narrative.

Once you know what a character wants, you can put problems in their way, and see how they go about solving those problems, in order to achieve their desire. Goal + obstacles = story.

If you want a perfect example of how desire + obstacle can create narrative, watch The Martian. Without giving too much away: Matt Damon’s character is stuck on Mars, and his goal is to survive long enough for somebody from earth to send a rescue mission. It’s a hostile environment, where the obstacles are stacked against him. Each time he crosses an obstacle, another one rears its head. Not only does this create narrative drive, it also gives the narrative a sense of tension and release, as we follow the character’s desire to live.

‘At some point, everything’s going to south on you… and you’re going to say, this is it. This is how I end. Now you can either accept that, or you can get to work. That’s all it is. You just begin. You do the math. You solve one problem – and you solve the next one – and then the next. And if you solve enough problems, you get to come home.’ – The Martian

2. Make characters interact.

It can be so easy to write long extensive scenes in which a character sits in a room, possibly looking out of a rain-blurred window, contemplating life. I get it. Let’s face it – that’s quite possibly what you, the writer, are doing a lot of during the writing process, and they do say to write about what you know…

I wrote a whole novel where (for a significant chunk of it) the protagonist believes she’s the last person left alive on earth. The temptation to have her sit down and just think highly philosophical thoughts for long swathes of text was huge. But at the end of the day, that rarely makes good narrative. And if you’re stuck, maybe it’s because nothing is actually happening in your book. I recently spoke to a friend who was having trouble with a scene she was writing for precisely this reason. Her character was simply standing by the window, raising the tension and giving the writer a chance to describe the carpet tiles in great lyrical depth.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with lyrical description. Some of my favourite writers have this lyrical gift in spades. But when you do describe something in great detail, it has to be a choice, and not just as a way of stalling because you’re not sure what’s going to happen next.

My advice to my friend? Bring another character into the scene. Force them to interact.

Of course, how they interact will depend on who the other character is, and on their relationship to character number one. And I mean that in narrative terms, not just in terms of whether they’re the character’s sister or boyfriend or a distant stranger.

Let’s say that Character A (the one previously sitting and pondering the rain) is the protagonist. What is Character B’s purpose in the story? Are they there to assist the protagonist? Or are they the antagonist? If they’re the antagonist, then maybe they’re the one providing those obstacles we talked about in the previous section. (Think of the way a villain tries to foil the hero in a superhero film.) If they’re there to assist the protagonist, maybe the two of them are overcoming an obstacle together (think Thelma & Louise).

Still stuck on how to make your characters interact? Give them a task to accomplish together. It can be as simple as cooking a meal, but the way they interact during it will reveal a lot about their characters, and about their relationship with one another.

3. Start a fire.

If that interaction still isn’t getting you anywhere, then try something more dramatic. Give your character or characters a catastrophic event to react to. The beauty of rewriting is that you can always cut this event later, if you decide it really doesn’t fit your plot. But it can be a useful tool to get you past a difficult stage in the writing process.

In her book A Novel in a Year (based on the newspaper column of the same name), Louise Doughty advises crashing an aeroplane into a hospital, then seeing how the characters respond. Obviously that’s a hugely dramatic event, involving a whole community. But if you wanted to make it smaller and more contained, then why not start a fire? (In your novel, of course – not on your desk.) It could be a big house-burning-down sort of fire, or it could be a small more easily containable fire. Either way, it’s the sort of emergency that brings character traits to the fore, and heightens relationships between them.

I always think that writing fiction is somewhere between finely tuned craft and childlike play. So don’t be afraid to play around with your characters. Put them in unusual situations. Write fan fiction of your own novel, if it helps, to see how your characters would respond in different circumstances. You can always pick and choose the bits you want to include later on.

4. Skip back a bit.

It’s a well-known truism that, if you run into problems on page 200 of your manuscript, the likelihood is that the original problem started on page 100.

I forget who originally said this, but it’s certainly proven true for me – not just in fiction, but sometimes in poetry as well, albeit on a smaller scale. Often, the bit you’re struggling on isn’t the problem. The problem is buried somewhere much earlier.

I suppose it’s a bit like catching a cold. The first time you cough or sneeze isn’t the first instant you’ve caught the cold. The illness has probably been there for a few days or hours, incubating as your immune system begins its attempts to combat it, before the symptoms show themselves. It’s the same with fiction. Something happens early on in the novel, or your character makes a wrong choice, and suddenly 100 pages later, you find you’ve reached the dead end.

The trick is working out what that choice was. Try working out what events led to the scene that you’re stuck on. Can you change one of them slightly?

Over-simplified example: a girl is walking through a forest, on the way to her grandmother’s house. She sees a wolf, and wisely avoids talking to him, because she’s always been told to avoid wolves. There’s a moment of dramatic tension where you think she’s going to break her promise to her mother, but because she’s the hero, she never does – so she continues through the wood till she arrives at the cottage. When she gets there, she has tea with her grandmother. Suddenly, you’re stuck in a scene where Red Riding Hood and her grandmother are making smalltalk about the weather and nothing is really happening very much.

You have two options.

Option 1 is to introduce a big dramatic event, such as a fire. Maybe a spark from the grate ignites the rug, and before you know it the whole cottage is in flames, forcing them out into the forest, and perhaps straight into the arms of the prowling wolf, who has followed Red Riding Hood to the cottage. Suddenly, you have a crisis, and a problem they have to solve. You have a story again.

Option 2 is to go back to a point earlier in the story, where Red Riding Hood meets the wolf. Instead of ignoring him as she’s been told to do, she tells the wolf all about where she’s headed, giving him time to reach Grandmother’s cottage ahead of her, to eat Grandmother, and assume his disguise. We change the protagonist’s actions, and by doing so also introduce a character flaw: her reckless disobedience (the flaw which, in the Roald Dahl version of the story, becomes her saving grace). Once again, we now have a story.

5. Skip forward.

If you’ve tried looking backwards in the story, and got nowhere, then you’re always free to go the other way, and to skip forwards. After all, there’s no rule saying you have to write your novel chronologically. It’s perfectly acceptable to write the bits where you know what’s going to happen, and then fill in the blanks later.

(Programmes like Scrivener are particularly useful for this, as they allow you to segment your writing project into scenes and chapters, then move them around if necessary.)

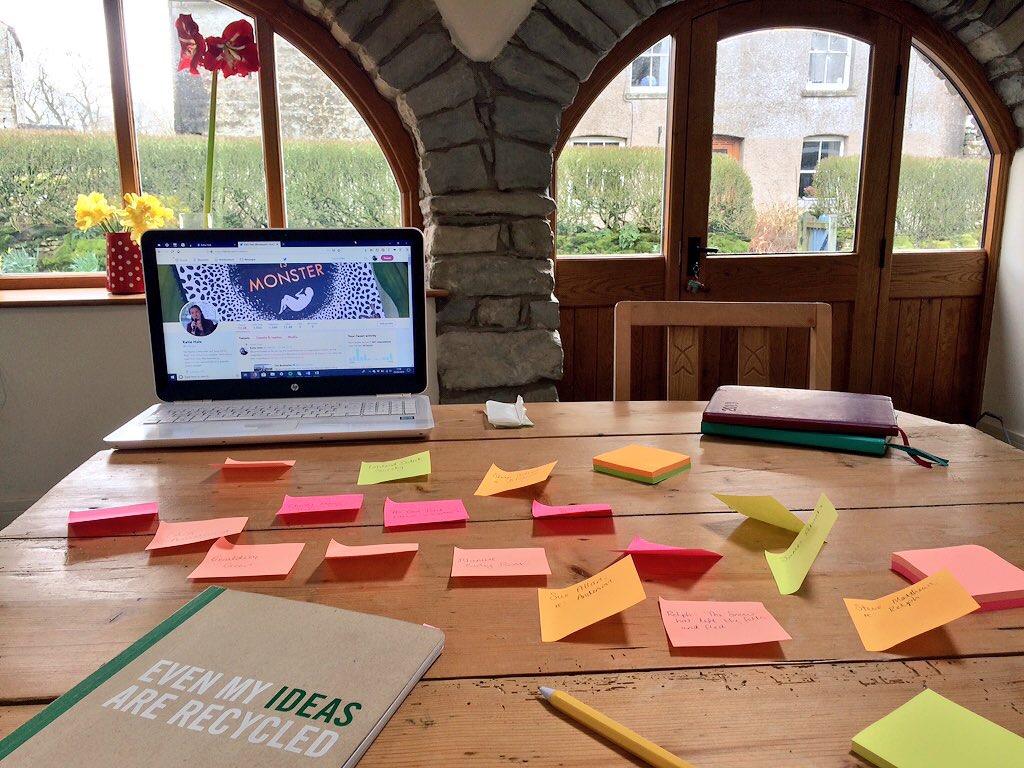

You might not even know what order the scenes go in just yet. That’s also fine. When I was drafting My Name is Monster, while I did have a vague notion of the direction of the story, there were definitely bits that I moved from one part of the novel to another during the writing process. At one point I had the whole manuscript printed out and arranged by scene on my living room floor, with all my furniture pushed back to the walls, so I could rearrange the order by moving the pages around from one place to another.

So if you’re stuck? Move on and write something else. You may get to a scene later on, where you realise X needs to have happened already in order for Y to happen later. Suddenly, you realise X is the missing ingredient to the scene you were stuck with all along.

Whatever happens, the important thing is to not let it get the better of you. Don’t give up – and keep writing!